Land-use

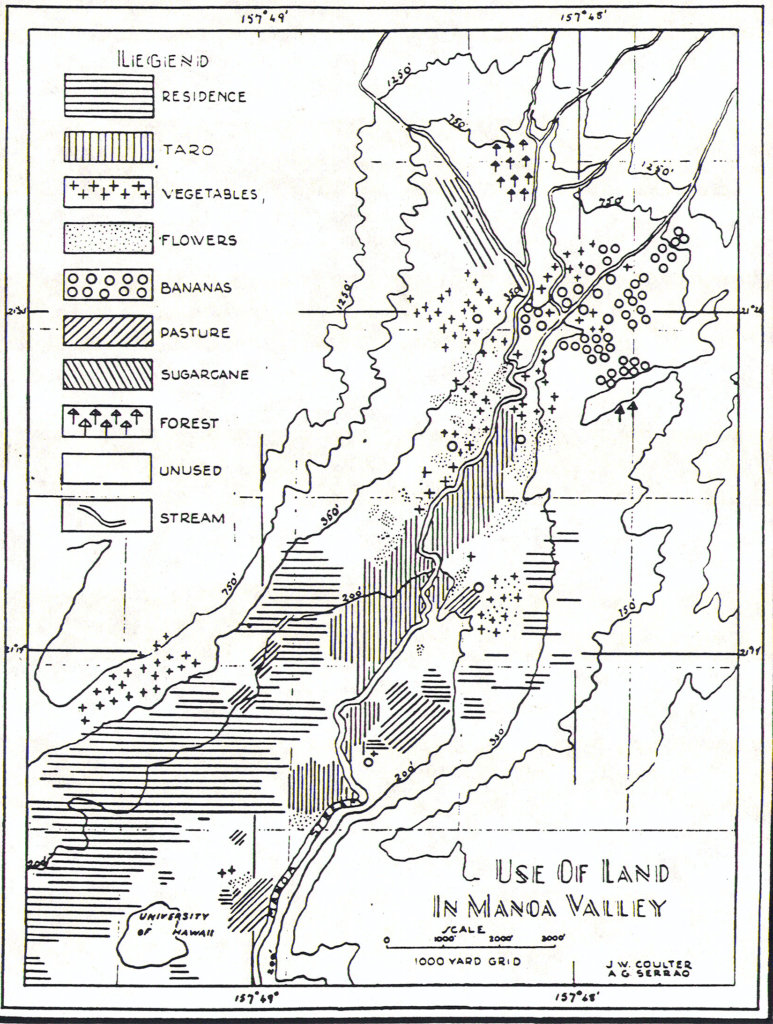

Mānoa Valley has a long history as a place of agriculture. It is only in the last fifty years and in particular the two decades following World War II that agriculture vanished from the valley. Increased population and Mānoa’s proximity to the growing city of Honolulu transformed the valley into one of the most desirable residential neighborhoods on the island.

After Captain James Cook made the first Western contact with the Hawaiian Islands in 1778, ships from foreign ports began to arrive. While ships found the islands an invaluable port of call, contact with foreigners brought on a swift decline of the indigenous population due to introduced disease and rapid change.

When Captain George Vancouver, trekked inland from Waikīkī in 1792, he observed the agricultural activity in lower Mānoa: We found the land to be in a high state of cultivation, mostly under the immediate crops of taro and abounding with a variety of wild fowl chiefly of the duck kind…

Among the many changes brought to the islands by the immigration of foreigners, were new agricultural interests. Coffee, sugar, and pineapple, three of Hawai‘i’s most important crops, were first commercially planted in Mānoa as part of a venture by Chief Boki and his British partner, John Wilkinson, in 1825. They are said to have planted seven acres of sugar above Punahou hill and started a coffee nursery just above Ka‘aipū with plants from Rio de Janeiro. Pineapple was later added. After a year, Wilkinson died of a fever and Boki lost interest. However, seeds from the Mānoa coffee plants were used to start growing coffee on Kaua‘i and in Kona, now world-famous for its coffee.

It has been suggested that the chief Kamehameha may have had a residence in the valley, but historical evidence is unclear.

In the 19th century, particularly after the Mahele, foreigners also found Mānoa an attractive neighborhood. Besides the cool climate, it was a pastoral, rural environment, close to Honolulu. A few large homes were built in the valley some of them used as summer retreats to escape the heat of downtown Honolulu. By the 1880s, Chinese taro farmers largely replaced Hawaiian taro farmers, but the valley was still very much a place of agriculture:

At the summit of the road (at Pu‘u Pueo) the whole valley opens out to view, the extensive flat area set out in taro looking like a huge checkerboard, with its symmetrical emerald squares in the middle ground surrounded by pasture fields on the slopes of the guarding hills. . . . (Thrum 110)

By the end of the century, about half of the taro farmers in Honolulu were Chinese, and the Chinese did 80 percent of the poi manufacturing. A sizeable population of Chinese settled in the valley and many independent Japanese farmers also moved into the upper valley, growing table vegetables and some flowers. Several small dairy farms were also established in Mānoa.

In 1886, Seaview Tract opened near the present-day University of Hawai‘i as a small residential area. It had little impact on the upland farms. But the College Hills Tract, a major development in 1901 by Punahou School signaled the beginning of the valley’s transformation. An important added attraction of the tract was the extension of the trolley line to mid-Mānoa.

Mānoa was slowly transformed into a residential neighborhood in the first half of the 20th century. In the 1950s there were still a few small farms in the upper valley growing vegetables and flowers. Today, agriculture has all but vanished from Mānoa Valley, but Mānoa still remains a multi-cultural neighborhood and one of O‘ahu’s most desired residential areas.